I read somewhere that wealthier families in ancient Rome were able to siphon off water from the main aqueducts leading into town, but they would take the water where it would collect in cisterns. Pipes went forth from the cisterns at three heights; the highest piping went to the private homes, the middle pipes went to the public baths, and the lowest pipes went to public drinking water. This was so that in times of water shortage, the more essential needs of the city would be met. On the flip side, if you lived in a wealthy house where your water dried up on occasion, you would probably be assured of getting the cleanest water. The dregs would naturally accumulate toward the bottom of the cisterns!

How much water did people through history actually drink?

We hear today that people need to drink lots of water daily (anywhere up to 100 oz.) for proper hydration – despite the fact that most people live rather sedentary lives in which perspiring or strenuous exercise are only a small part of a daily routine.

We hear today that people need to drink lots of water daily (anywhere up to 100 oz.) for proper hydration – despite the fact that most people live rather sedentary lives in which perspiring or strenuous exercise are only a small part of a daily routine.

With that in mind, I have a question or two: how much did people from history actually drink? Also, were they sufficiently hydrated?

A few observations first:

- Civilizations, cities, and towns typically emerged near constant supplies of potable water (e.g. rivers)

- Certain civilizations (e.g. Romans) were able to supplement water supplies with outside water quantities that rivaled the amount of water used per person today

- At certain points in history, water potability either decreased or was perceived to be decreased so that preferred beverages came from other sources (e.g. beer)

At least some societies were able to enjoy an abundance of water even when not close to an original water source. The great example I can think of is that of Nimes, France, where (according to my notes) each individual had access to 100 gallons of water per day(!). To put this in perspective, the average daily use by modern Americans is 176 gallons per day. But even if some civilizations could readily drink water, it seems that it must have been rather difficult for people living in more rural areas – or traveling through them – to maintain proper hydration. This must have been especially true in areas where natural water supplies were tainted. If we consider an example of travelers during the Middle Ages going on pilgrimage, should we presume that dehydration – or even death thereof – was a common problem? With increased perspiration from travel, increased climate during the medieval warm period, and scarcity of water sources, how did they ever manage to survive? Of course, this would not have been a problem confined to the Middle Ages, but would have been present in any age and place where clean water was not in adequate supply.

While I do not recall hearing about any specific historical deaths resulting explicitly from dehydration*, I do not think it unreasonable to think that this would have been the direct cause of a significant percentage of deaths. After all, when disease strikes, fatalities result not so much because of the disease itself but because of the inability to replenish and retain fluids. But setting aside cases of infirmity, was hydration recognized as being an important part of all-around health? This is an open question.

* I recall, however, the case of over-hydration (allegedly) killing one individual – astronomer Tycho Brahe in 1601

Basic information on Roman aqueducts

The Roman aqueduct system is one of the most fascinating aspects of ancient Rome (in my opinion, of course). Not only did these create important infrastructures for city development, but they also projected the power of Roman authority well outside the walls of cities.

Oh, and they were terribly ambitious as well!

Using aqueducts, the Romans were able to transport water dozens of miles from its source to cities and towns where it was accessible to the masses. The general idea behind this system was gravity; using a sloped surface, water would flow downhill (ever-so-slightly) from Point A to Point B. One of the problems with this system was that at times the aqueduct would need to run across valleys, which meant the flow of water had to occasionally travel uphill. The Romans tackled this problem by using siphons: ducts that hugged the ground received the water that ran down one hill, and this caused enough pressure to push the water in front of it up the hill on the far side of the valley.

In smaller valleys, the Romans had the option of building large, arched aqueducts in lieu of using siphons. The simpler post-and-lintel system could have been used to create these, but they would have required many more vertical supports than needed by the more practical arch (the Romans, of course, are known for exploiting the arch in their architecture). The arches were constructed using wooden scaffolding called “centering”.

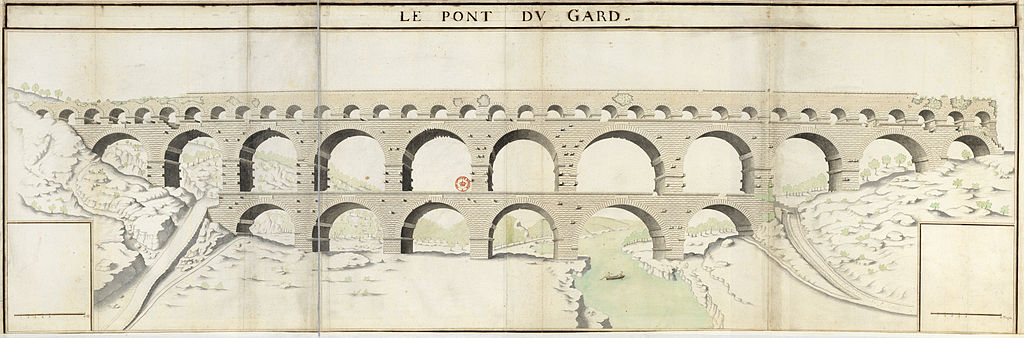

These structures, which allowed the water to flow downward at a constant slope, had an effect which may have been equal to that of their practical use: they fostered the idea of Roman authority and might in lands far outside Rome itself. Imagine being a non-Roman who wandered into southern France circa 10 B.C. and seeing the magnificent Pont du Gard (see photo) straddling the river. Not only are the blocks of stone that make up the arches and piers massive in size, but there are three tiers of arcades which stretch a vast distance between hills. How would you have reacted?

For those who had never been to Rome (or any major Roman city), these kinds of structures would have astounded. What kind of civilization could create such works? What kind of power did they possess? The visual fireworks put on permanent display by these aqueducts would have impressed all who saw them for the first time. Thus, their utility was matched by their symbolic importance in helping to elevate the Roman Empire to heights that may have been previously unknown in the ancient world.

For more in-depth background information on aqueducts, see the site of W.D. Schram.