William II Canynges (probably born about 1399) was the son of a renowned Mayor of Bristol.

A city mayor during the 15th century had to be a very wealthy man indeed. The honour that the city had bestowed on him often resulted in a year-long parade of ceremonies. Additionally, a very strong personality was essential with which to impose his authority over the hardy race of determined townsmen of lesser means. So it was that a city Mayor was more often than not chosen from the wealthiest and most successful merchant in town The down side to this was that the position of Mayor meant that the incumbent had no time for his own business or private concerns. However, during his year in office he belonged to the city; and the city, except for the King’s prerogatives, belonged to him.

It is not really surprising then, that Bristol chose William Canynges as Mayor on five occasions. His fame as a merchant was well known, not just in his own town but throughout Europe, for he built and operated a fleet that included some of the largest merchant-vessels then sailing under the English flag. He employed at times almost a thousand men on his far flung enterprises largely consisting of exporting wheat, wine and quantities of cloth (especially the brightly coloured cloth to Iceland,), and introduced to English civilisation such products as glasses, combs, caps and shoes, hardware and small beer.

From Iceland came fresh fish, usually salted on the journey home, and iron-hard codfish. A merchant whose vessel brought in ?600 cargo of fish could expect to sell them at market for a sum in excess of 1,000 [in currency].

Canynges possessed a fleet of ten vessels totaling some 3,000 tons (laden) crewed by 800 sailors. The largest, the “Mary and John”, was 900 tons and cost 4,000 marks to build. It was the marvel of its time, for most other vessels from Italy and Spain were far smaller.

Freight rates too were so profitable that Canynges was regularly able to keep all of his ships fully employed and would normally expect to enjoy a gross return of 10,000 in a single year. There were risks, of course; even if a ship did survive storms and other natural catastrophes, it might well be taken by pirates (a common hazard for seafarers of this time). Or, it might be tied up for months, in time of war, by being requisitioned by the King to defend England’s coastline.

Canynges minimized this final problem by lavishly entertaining King Edward at his mansion and made a present of a large sum of money to his monarch. This present to King Edward would be well rewarded in return. Edward IV was the first English King to actively encourage shipbuilding, introducing incentives such as a first voyage free of customs duties, and forbidding the carrying of imports in foreign vessels if a suitable English ship was available.

In addition, Canynges’ city of Bristol would receive a significant number of Royal privileges. In 1480, another Bristol merchant, John Jay would send two ships out into the wild Atlantic in search of “The Ile of Brasile”. After two months the expedition would be forced to return to an Irish port. A second expedition a year later fared little better, but eventually a man named John Cabot arrived in Bristol, and the rest is history.

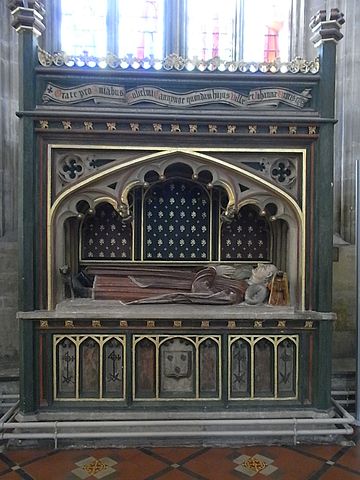

William Canynges was a man of strong religious conviction at a time when the power of the Church was coming under quite serious opposition. He rebuilt St.Mary Redcliffe, one of the loveliest churches in England, and died in 1474 humbly serving within Holy orders.

This post was originally published as a discussion topic July 20, 2006. The post was edited for clarity and grammar.