I re-watched a beautifully-produced documentary that chronicled the Pilgrims’ plight in the early seventeenth century as they struggled first against the English king, and later against natural forces in the New World as they established their colony at Plymouth. The documentary highlighted several ideas that I think are quite significant and intriguing, but that are also either ignored or unknown in our collective understanding of the Pilgrims today.

With this in mind, here are four important and interesting facts about the Pilgrims’ story.

The Pilgrims were “Separatist” outlaws

As part of the English Separatist Church, they extracted themselves from the Church of England in 1607, against English law. This made them not only religious outsiders, but political outsiders as well, and they risked their own freedom, and possibly their very lives, by worshiping outside the approved dictates of the Church of England. They found their immediate solution to this problem not in the New World, but in Holland. In 1608, they were able to escape England and move to the Dutch city of Leiden, where they were able to worship freely, albeit in unfamiliar surroundings. After spending over a decade trying to establish a community in Leiden, they had misgivings and decided to change course and build their community in America.

When the time came to make the historic voyage in September 1620, only 102 passengers were on board. Of these, less that half consisted of adult men, and many of the passengers were children. Some of the people on board were not even members of the religious sect, but instead were “strangers”, or members of the Mayflower’s crew.

We might draw parallels between this group and other religiously “fanatical” groups, such as Jim Jones’ cult, in the sense that their religious motivations compelled them to break from their homeland in search of autonomy. While most sectarian experiments like these are likely doomed to long-term failure, it’s quite phenomenal to realize that the United States has its own popular day to celebrate its own religious “separatists” from the early seventeenth century.

The reasons why they left for America

The general reason for the Pilgrim’s journey was religious freedom, but we know that could have enjoyed this by simply remaining put in Leiden. Why, then, did they pick up after a decade and move to the New World? The first reason was that although they were culturally English, they realized their children were growing up as children of the Netherlands, rather than children of England. The Pilgrims wanted to have some say in the national identity of their children, and they were losing this battle in Leiden.

The second reason was the tumultuous political situation in Europe at the time which was about to wreak havoc on the continent. The Thirty Years’ War, which lasted from 1618-1648, was one of the bloodiest conflicts in world history, killing millions of people. As the war was beginning, the Pilgrims decided to chart their future course in a place safe from harm as an English colony in America. There, they could practice their religion as they chose, while at the same time building a society within the cultural framework of their own choosing.

The Pilgrims’ original “Thanksgiving” was a minor event at the time

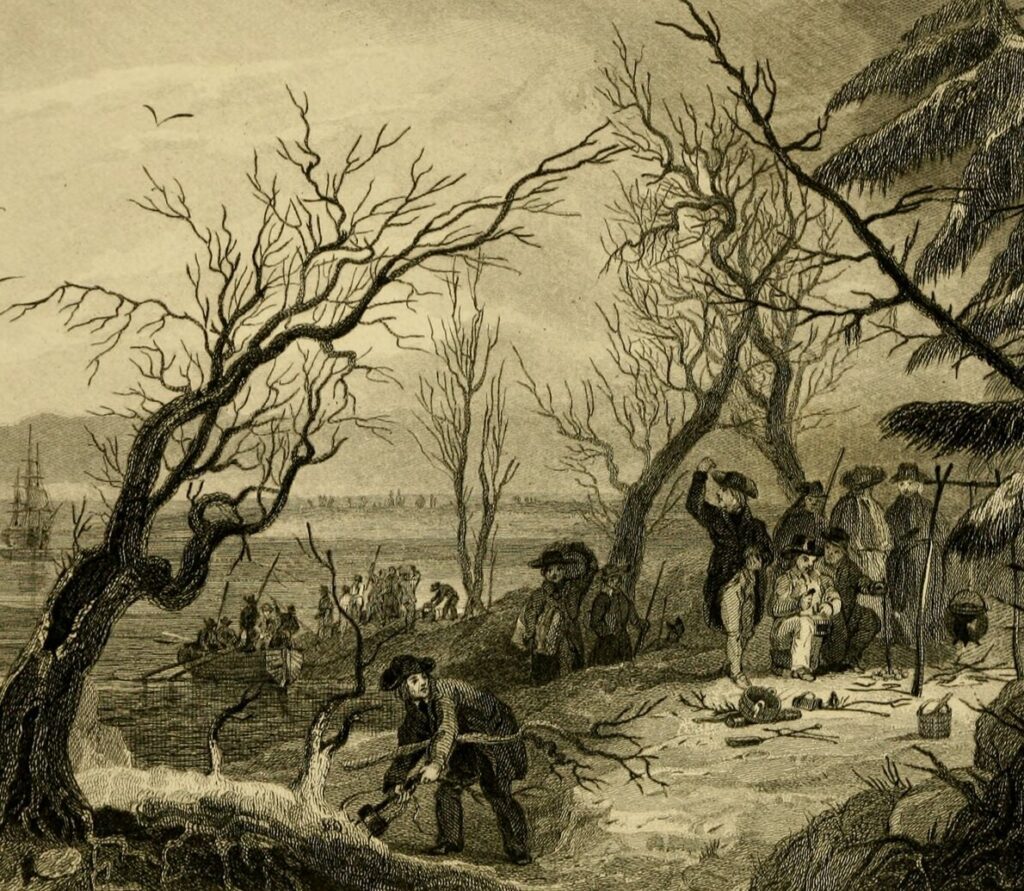

After arriving at Plymouth in November 1620, the Pilgrims immediately faced immense challenges. Not only did they need to find food and other supplies in unfamiliar surroundings, but they also had to build shelter, care for their sick, and be on guard against any hostile groups in the area.

The first few months were brutal. By Spring of 1621, death had come for half of them, and the outlook must have seemed almost hopeless. However, in mid-March, an incredibly fortunate meeting took place when a group of native Wampanoag Indians came across the village. Within this group was a young Wampanoag named Tisquantum (Samoset), who walked into the settlement and greeted the Pilgrims in English. It turned out that Tisquantum had previously been captured by Europeans and transported to the continent, where he remained until returning to America in 1619. In fact, he had previously lived in the same spot now occupied by the Pilgrims before a plague wiped out the rest of his townsfolk a few years earlier.

With Tisquantum serving as interpreter between the two sides, the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag were able to establish a treaty to avoid harming each other, and to aid the other in case of trouble. In addition, Tisquantum remained with the fledgling village to help them plant crops in the Spring. Although death continued to visit the Pilgrim settlement that summer, by Autumn the community had managed to survive and reap a successful harvest. Around October, a group of 90 Wampanoag Indians arrived at Plymouth and, according to a brief account by Edward Winslow, celebrated the Fall bounty with the Pilgrims. It was not called Thanksgiving at that time, though it did extend over the course of three days and was accompanied by games and food provided by both Pilgrims and the Wampanoag.

The Pilgrim’s story took on mythical status thanks to political propaganda around the U.S. Civil War

Little would have been known about the the story of the Pilgrims without the journal of William Bradford, one of the key separatists who arrived on the Mayflower and who would also become the settlement’s second governor. In 1630, Bradford penned his memoirs of the settlement’s founding and growth over the previous decade in a work entitled, Of Plymouth Plantation. After Bradford’s death, the work was passed down through his family until it made its way to a Boston library in 1767. It was then taken by the British and later considered to be lost until it resurfaced in the library of the Bishop of London many decades later.

Interest in the colonial roots of the United States came to the forefront in the mid-nineteenth century as the debate over America’s beginnings reflected the ongoing political divide leading up to the U.S. Civil War. Was the settlement at Plymouth in the North the true origin story of the nation, or was it the settlement at Jamestown in the South? After Bradford’s work was located in 1855, a copy was made and sent to Boston, starting a new flash of excitement over the Pilgrims’ place in America’s story. Only a few years later, Abraham would solidify this renewed interest in a pronouncement which made the last Thursday of November Thanksgiving Day, a holiday to honor the contributions of those first Plymouth colonists.

Once the Pilgrims’ place in America’s origin story was set, the U.S. never looked back.

Watch The Pilgrims: A Documentary Film by Ric Burns at PBS.org