In my opinion, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 violated the precepts of justice in at least three ways. In a nutshell, the Act gave legal force to southern slave owners to retrieve their slaves who escaped to the North. The Act was important to southerners because it was seen as a kind of quid pro quo; in exchange for giving slave owners a sense of security, the South agreed not to secede.

The first way the Fugitive Slave Act violated justice was in its abuse of the Separation of Powers, in that it allowed for a connection between judicial decisions and enforcement of those decisions. At a slave owner’s hearing to reclaim a slave, a commissioner might be paid $10 for keeping a person in shackles, and only $5 to set him free. Over first 15 months of the FSA, 84 cases returned the alleged fugitives to owners, while only five were let go. This suggests that commissioners were more interested in personal financial gain than the Constitutional rights of free blacks.

The second reason the Act was unjust was because alleged fugitives could not offer testimony into evidence. This treated all blacks as slaves for the sake of the hearing, and thereby took away the right of free blacks, without due process, who could otherwise testify in court.

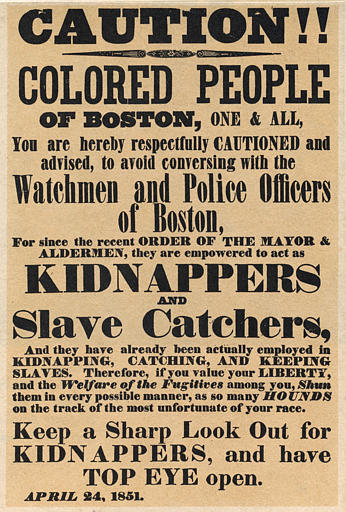

The third way the Act was wrong was that it promoted a policy of violating the rights of free blacks. Slave catching became a profitable business and didn’t always distinguish between slave and free. The Gap Gang, which operated before the Act took effect, was one such group from Pennsylvania that did not often distinguish between slave and free. A startling message, found on a counterfeiter, directed to “go among the niggers, find their marks and scars, send good descriptions of them and I’ll find owners.”

So why did the North enact such as law? Perhaps it was agreed to in haste out of a desire to see the South pacified. As we now well know, even this attempt to quell the storm of dissent was short-lived.

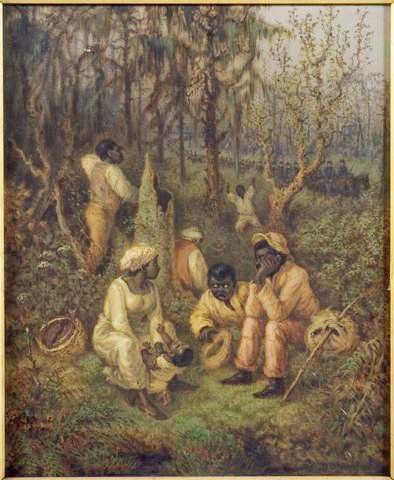

Top image: Eastman Johnson, A Ride for Liberty — The Fugitive Slaves, c. 1862, Brooklyn Museum.

Sources

- Thomas P. Slaughter, Bloody Dawn: The Christiana Riot and Racial Violence in the Antebellum North (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994).

- Philip S. Foner, History of Black Americans From the Compromise of 1850 to the End of the Civil War (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1983).