We hear today that people need to drink lots of water daily (anywhere up to 100 oz.) for proper hydration – despite the fact that most people live rather sedentary lives in which perspiring or strenuous exercise are only a small part of a daily routine.

We hear today that people need to drink lots of water daily (anywhere up to 100 oz.) for proper hydration – despite the fact that most people live rather sedentary lives in which perspiring or strenuous exercise are only a small part of a daily routine.

With that in mind, I have a question or two: how much did people from history actually drink? Also, were they sufficiently hydrated?

A few observations first:

- Civilizations, cities, and towns typically emerged near constant supplies of potable water (e.g. rivers)

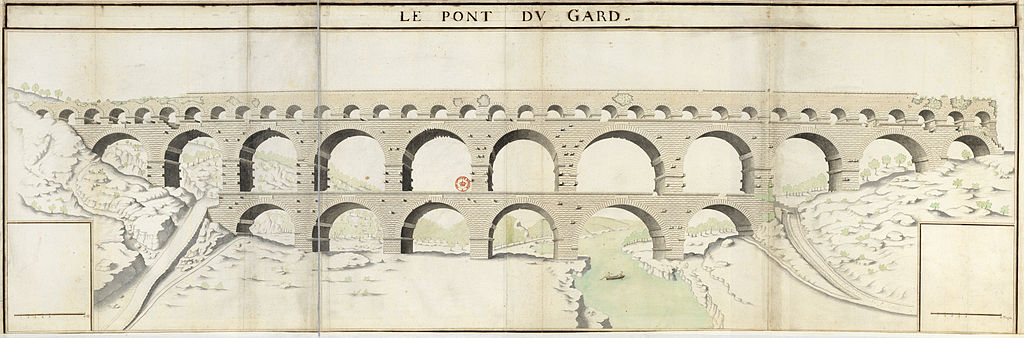

- Certain civilizations (e.g. Romans) were able to supplement water supplies with outside water quantities that rivaled the amount of water used per person today

- At certain points in history, water potability either decreased or was perceived to be decreased so that preferred beverages came from other sources (e.g. beer)

At least some societies were able to enjoy an abundance of water even when not close to an original water source. The great example I can think of is that of Nimes, France, where (according to my notes) each individual had access to 100 gallons of water per day(!). To put this in perspective, the average daily use by modern Americans is 176 gallons per day. But even if some civilizations could readily drink water, it seems that it must have been rather difficult for people living in more rural areas – or traveling through them – to maintain proper hydration. This must have been especially true in areas where natural water supplies were tainted. If we consider an example of travelers during the Middle Ages going on pilgrimage, should we presume that dehydration – or even death thereof – was a common problem? With increased perspiration from travel, increased climate during the medieval warm period, and scarcity of water sources, how did they ever manage to survive? Of course, this would not have been a problem confined to the Middle Ages, but would have been present in any age and place where clean water was not in adequate supply.

While I do not recall hearing about any specific historical deaths resulting explicitly from dehydration*, I do not think it unreasonable to think that this would have been the direct cause of a significant percentage of deaths. After all, when disease strikes, fatalities result not so much because of the disease itself but because of the inability to replenish and retain fluids. But setting aside cases of infirmity, was hydration recognized as being an important part of all-around health? This is an open question.

* I recall, however, the case of over-hydration (allegedly) killing one individual – astronomer Tycho Brahe in 1601